Published on Saturday, November 7, 2020 by Agitator Co-operative

Agitator Lyceum Series

Concretizing “Young People”: Critically Rethinking Age in a Global Age

Based on an interview with Dr. Talmadge Wright.

by Josh Mei, Agitator member

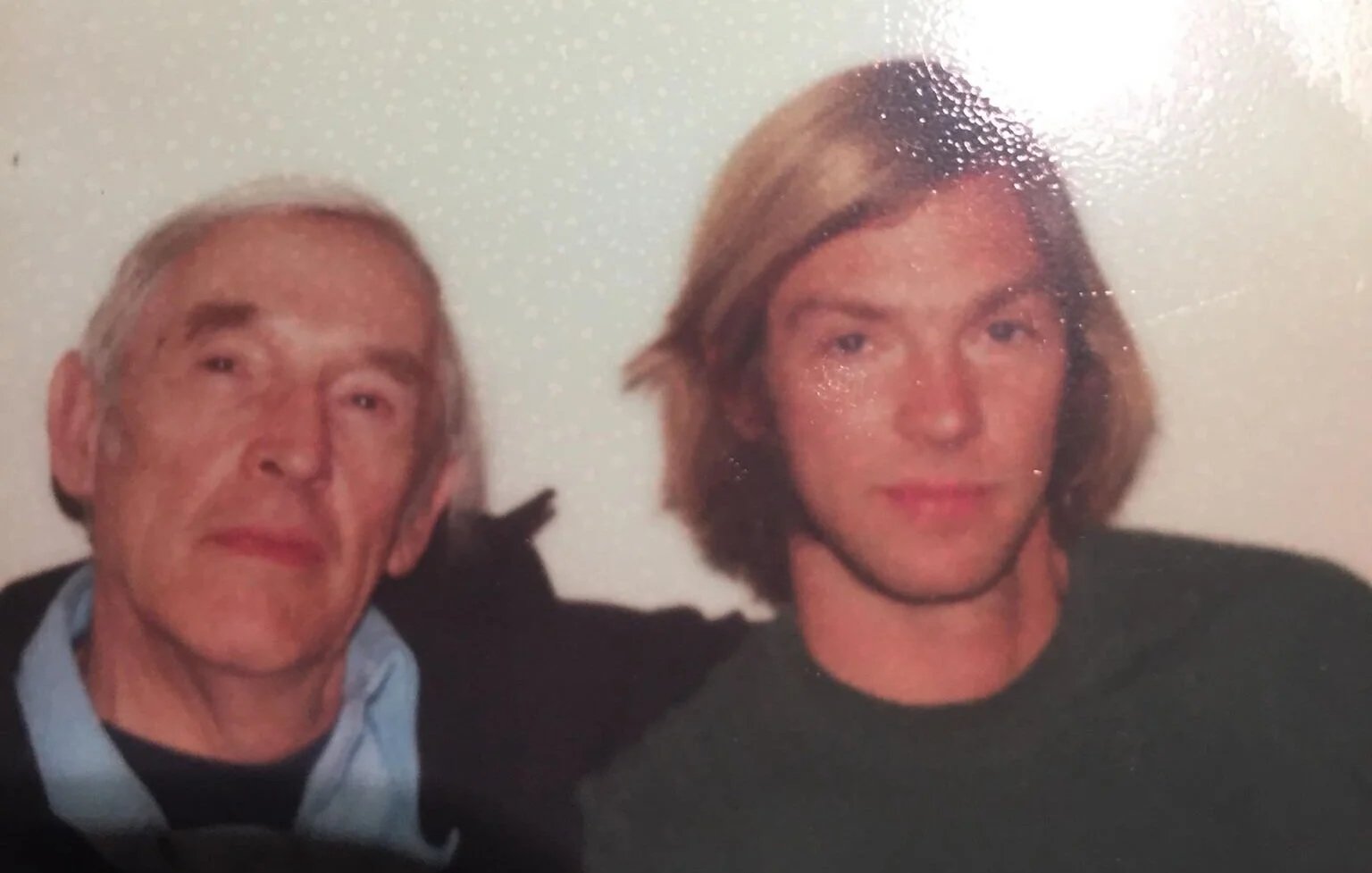

Dr. Talmadge Wright (R) with his father, 1972.

What does “young people” mean? Does it simply refer to a group of individuals whose age is less than that of others, or does it also imply additional things? Dr. Talmadge Wright thinks it should be the latter. Currently Lecturer in Sociology at Sonoma State University and Professor Emeritus in Sociology at Loyola University Chicago, his areas of expertise span homelessness, social movements, mass media and popular culture, as well as digital gaming, to name a few. Dr. Wright was my sociology professor and mentor during my undergraduate years at Loyola. He taught my social theory and 60s social movements classes, along with providing me guidance for my senior thesis about Twitch.tv. Having interviewed him over Zoom in mid-July, we will discuss the problem of “young people” and provide sociological critiques of the term’s use.

The year 2020 is marked by not only a global pandemic and economic crisis, but also widespread global upheavals protesting the racist police institution’s murdering of black people in America, sparked by George Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020. Although the age demographic of current Black Lives Matter protesters is mixed, we cannot deny that young people still constitute a huge part, even in historical uprisings:

“We know that people who make revolutions are not old people. They’re young people. We know that the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, even the Cuban Revolution, were made by people under the age of 40. Many were in their mid-20s. If you look at what went on in Syria, most of the fighters were in their 20s.”

Given their significant role in enacting positive societal changes, it is important to analyze what “young people” means.

We center first on how the media present “young people” to the public. To avoid abstraction, the media includes social media like Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit, as well as established media sources like CNN, Fox News, and The Guardian. More often than not, people of the media, professional journalists included, resort to calling people who are young as “young people” or lumping them into codified labels like Millennials. What this does, however, is it compartmentalizes different people into the same categories. This can be problematic according to Dr. Wright:

“Not every young person has the same experience. I’m the same generation as Dick Cheney is, but I sure as hell ain’t no Dick Cheney. His experience with his group is quite different from mine, so I’m reluctant to tag young people as ‘young people’ because that falls into the marketing niche of Millennials vs. Generation X vs. Generation Z, which to me is much more of a marketing technique to divide populations, rather than to increase their solidarity.”

If abstracting age is a marketing technique, as Dr. Wright argues, then there must be something marketed for and somebody marketed to. In the age of consumer capitalism, marketing firms devise tactics and strategies to sell not only products like music and clothes, but also ideas like stability and independence, to consumers, and target populations are usually people under 40. In other words, “young people.” It follows then that there is an imperative to divide young people into more subcategories, as there are “needs” each subcategory has that consumer capitalism can apparently fulfill. Likewise, contemporary journalism has a similar need to grab people’s attention. As society’s workings can bombard us in many directions, so too does journalism have to evolve to make itself stand out and be worth our time: “Journalism has to tell a story. They have a certain limited timeframe to do it in. They are not sociologists. They are not anthropologists. They’re telling a story. When you tell stories, oftentimes the temptation is to reduce the story to a digestible bite that you feel the audience can understand and select.” With concision comes a lack of nuance, and with a lack of nuance comes abstraction.

Having the abstract without the concrete can lead to the blind belief of ideas that the media present to us in ageist remarks many take to be normal and thus “natural.” It also reinforces the appeal of essentialism, the doctrine that everything has an essence, something special to it, without which it would not be itself. The problem with the essentialist mode of thought is that the essence is the thing’s defining factor, and everything else is inferior in importance to define the thing, if other “nonessential” factors are allowed to merit any significance at all. Many people simply do not question the factuality of what we consider to be something’s defining factor. But we should not yield reality to essentialist thinking, since it enforces ageist remarks directed at groups of people, young or old. It goes without saying there exists the rhetoric of Millennials being entitled and lazy, but we have to ask whether that is true, whether that applies to everybody in the age group, and whether it is fair to define people in those terms. If one says yes to all three, then, according to Dr. Wright, “It becomes a myth that people use to protect their psychological needs for stability, order, and rationalizations.” And accepting these stereotypes as truth does more harm than good.

Those are all reasons to reconceptualize and concretize our notions of age and “young people.” Nobody lives in a vacuum. We live in a changing world, a world where its material conditions have big impacts on people’s life chances. Suburbanization over the decades in America not only changed the demographics of urban and rural areas, but it also changed the locations of jobs and the kinds of jobs we have, a shift from manufacturing to the service sectors. Not surprisingly, these phenomena impact young people as a result:

“With young folks, they generally don’t own property. They’re usually renters. They’re more subjected to: economic oppression in the sense of not having capital to fall back on, unless they have wealthy parents; having unstable living arrangements, oftentimes living with other folks in the same units; and oftentimes facing really low salaries at any kind of service jobs that they might get, not unlike people of color, who are often stuck in these secondary labor markets.”

In addition to material conditions, we also have to consider the different ages young people are in, as well as the different social locations (e.g., race, class, gender, sexual orientation) and social interactions they have: “There’s a difference if you’re in high school, elementary school, or college. I think that each of these age groups has a specific experience of their communities, of their institutions, of their people around them.” Furthermore, the following are some questions we need to ask: “Who are they? Who are their parents? Who are their grandparents? Who are the people that are talking to them about what’s possible in the future and what’s not? What are their stresses and strains?” Only by considering the aforementioned factors are we one step closer to contextualizing and concretizing the abstract notion of “young people,” as well as dispelling its negative connotations.

Dr. Wright during his high school days with one of his science fair projects.

Dr. Wright was raised in Virginia and moved to California at the age of 13. Growing up, his family did not have any money, but his parents still supported him in his science fair projects and really pushed him to go to college for an education. Getting an education was a central part of his parents’ ideology. For that he is grateful because the level of support helped him to push through obstacles life had to offer, and this is one reason he believes not supporting young people is “one of the worst things we can do.” Of course, support for young people goes beyond moral and emotional ones. Having an education is crucial in 2020, especially with the “proliferation of news sources, social media and elsewhere,” that we not only “have both more possibility of getting more stories out that are more diversified,” but also “a lot more nonsense to go through that you didn’t have before.” The large amount of information various sources offer to the public likely muddles the truth, and it certainly takes “an education to understand what it is you’re looking at, what you are paying attention to.” He adds with a warning:

“If we don’t support the episteme over doxa, the idea of true knowledge over prejudice, what happens is we become more and more unable to differentiate what’s real from what’s not. I think the extreme example of that is Ted Kaczynski. When people start becoming delusional, hyper-individualist, they resort to violence, thinking that they’re right.”

And Dr. Wright is optimistic about young people leading the fight in the streets. In contrast to the 60s upheavals where, for example, the early feminist movement “was really divided along race and class lines,” young people and groups nowadays, particularly Black Lives Matter, are beginning to see the intersectionality of race, class, gender, and sexual issues. This in part has to do with young people’s quality of being understanding “because of the nature of social media, because of the nature of staying home and being on the computer, because of the inequalities they face that exist within the school system. They’re recognizing a lot of common interests.” What’s more, the pandemic ruptured the normality of many people’s busy lives and allowed them to pause and recognize all that is wrong with the world, one being the police murder of George Floyd. Equally, COVID-19’s potential to be almost omnipresent causes a feeling of psychological threat of death and annihilation not unlike the “nuclear threat that hung over us in the 1960s and 70s and 80s.” This same feeling also “creates the receptivity for the need to change and the need to do things differently than the way they are.” Let’s not waste this opportunity.

Mandela tabletop, 1973. Originally part of a larger project with an octagonal base with separate redwood panel each of which Dr. Wright carved out in Art Nouveau fashion. Sadly, the base disintegrated over the years.

Untitled sketch, 1971. Pen and ink on paper.

A section from "Stairwell Soundpiece I", a piece composed by Dr. Wright and Victor Lindsey. It was later performed in June 1978 on the 5th floor stairwell in the Social Science Tower on the University of California, Irvine campus. "The significance of this piece resides in the collective effort of the performers to produce multiple meanings in a 'functional' space designed to only contain a single meaning (stairwell-fire escape)."

Performers of "Stairwell Soundpiece I".

Performers of "Stairwell Soundpiece I".

Screenshot of Dr. Wright's Sociology of Play class in World of Warcraft, featuring his toon and his students' avatars.

The shed in San Lorenzo Acopilco where Dr. Wright lived for a year and a half from 1980-1981 with his girlfriend. At 9,000 ft., the shed had a thin asbestos roof and concrete floor with no insulation. It was quite cold in the winter, and the fireplace was useless. He was writing his dissertation and teaching English in Mexico City.

Dr. Wright presenting his data on playing Counter-Strike to Microsoft's Research Division in Redmond, Washington.

As the newest, and youngest, member of Agitator, my experience with the group compared to those of my colleagues has been, in a word, short. But it is not impossible to make a connection between the topics in this article and what our co-op offers to advance young people’s potentials. As a worker co-operative, Agitator offers an alternative to the traditional workplace of employer and employee, since the traditional model is usually oppressive and exploitative to workers. And all of us at Agitator are workers, but we are also owners of the co-op. Agitator members’ relations with one another, however, are non-hierarchical and in equal standing, so all members have an input in how to run the co-op, without unreasonable repercussions like those of at-will employment. This aspect is simply absent in many jobs that young people hold, and at Agitator, we welcome new, daring, and even unconventional ideas. Even I was initially surprised when my colleagues took my thoughts into consideration, given my experience of the near-universal “my way or the highway” attitudes of previous bosses.

I have also been responsible for duties like putting together a one-day lineup of Instagram Live broadcasts, fundraising for our Patreon page, promoting local artists on social media, running the online shop, among other tasks. If I were asked one year ago whether I could imagine myself doing all these things, I would have said no. Other than the simple fact that I did not know about Agitator at that time and therefore was not a part of it, working a job that entailed one main, redundant, and soul-destroying role was simply the norm and my bleak reality. But all this demonstrates that another world is possible, and we are actually living in it. We just need to discover it and make it a reality. If we wish to make the world a better place, then we must listen to what young people have to contribute and implement those ideas, even if they disrupt the status quo and make us feel uncomfortable.